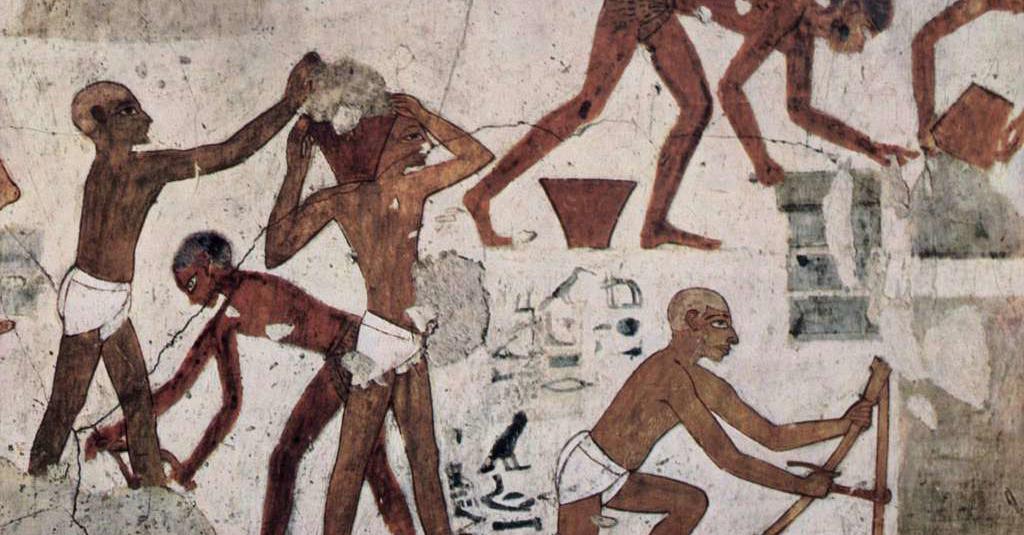

Slavery was and is, an ancient institution. Long before the time of Abraham, slavery was practiced in most ancient cultures, and it still exists today.

Mention of servants or slaves begins after the Flood, in the days of Shem, Ham and Japheth. Abraham had a son, Ishmael, by his Egyptian slave, Hagar. His nephew, Lot, was captured by a northern invading force, and marched off with his family, and the other inhabitants of Sodom, to become slaves to their captors. Three generations later, Joseph was sold by his brothers to Ishmaelite traders who took him to Egypt where he was sold to Potiphar as a slave. His descendants and those of his brothers were later enslaved, in spite of Joseph’s work of preventing famine in Egypt. Moses later told them,

“We were Pharaoh’s bondmen in Egypt; and the LORD brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand” (Deut. 6:21).

The Children of Israel were told to remember that they themselves were once oppressed slaves, and to think on that condition when dealing later with slaves and servants under their power. The covenant at Sinai established the principle of Israelites being released from slavery to another Israelite after 6 years. These slaves could remain with their master if they so chose. The Law stipulated that released slaves in Israel were to be provided for by their former masters.

“Thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith the LORD thy God hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him” (Deut. 15:14).

Foreign slaves, on the other hand, were usually held permanently—as property —which was the normal practice in the nations. Even these slaves, however, could enjoy the weekly Sabbath rest, and take part in the Feasts. After the Egyptian period of bondage, the Israelites also suffered with periods of Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian captivity.

Our New Testament record tells us of the role of slaves in the Roman Empire. People of all nations could be taken and made slaves in the society Paul was dealing with. There were a number of ways that people became slaves. The first was by capture as prisoners of war. The Romans began with the subjugation of their neighbours, but as their military prowess and success increased, so did the number of slaves under their control. The defeat of Carthage after the Third Punic War in 146 BC resulted in the enslavement of the entire population. Sometimes the victors in foreign wars sold their slaves to the Romans.

Kidnapping people to sell them became a problem in Augustus’ reign, and he attempted to put legislation in place to control it. Piracy was rampant in the Mediterranean. Even Julius Caesar was captured by pirates, but he was ransomed rather than being sold into slavery.

Roman law said that all children of slave women were slaves, regardless of who the father was, so the slave population automatically grew every year. The Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, saw an end to the great wars of conquest for the Romans, and allowed for a peaceful time for the spread of the Gospel, as Paul, Peter, Barnabas and others travelled the Roman roads.

Only the wealthy were able to support a slave-labour force, but the number of owners slowly increased. Approximately 600,000 slaves in 225 BC grew to number more than 2 million at the beginning of the first century. This represented about one-third of the population.

Paupers and those in debt could sell themselves—hopefully to a good master —for the food and shelter offered; or they could be sold into slavery by their creditors if they were unable to pay what they owed. They could also decide to sell their children. Children abandoned by their poor parents often were made slaves as well. It was a brutal system that permeated the empire, but one that everyone accepted.

Slaves were initially used for domestic work, but they soon came to be used for most tasks. Greeks were often used for tutoring or medical work because of their education. Criminals were most often punished by being sent to the mines and quarries for hard manual work. The harsh work conditions almost inevitably resulted in their death. It appears that the Apostle John wrote from the island of Patmos because he was sentenced to work in the mines.

Freeborn Romans were also known to sell themselves into slavery if it meant being given a position of power and influence. Claudius Felix, the Roman procurator, or governor, of Judea, to whom the Apostle Paul was sent after being taken into protective custody (Acts 22), apparently gained his position through his brother Marcus Antonius Pallas. Pallas was a favourite of the emperor Claudius, and he was a freedman—one who had been freed from slavery. Most imperial officials were slaves who often chose that life for its many benefits.

Slaves were at the lowest levels of Roman society, and had no rights, other than those given by their masters. Slaves were property and could be used for any purpose. Three terms were used for the divisions of society—ingenui—those who couldn’t be enslaved; libertini—slaves who had been manumitted—or released from slavery; and servi—those who were subject to slavery under Roman law. The majority of the workforce of the empire eventually came to be made up of slaves.

The adoption of Christianity as the state religion brought about some changes in the treatment of slaves, but did not do away with the institution. Jesus and the Apostle Paul both spoke of believers making the best of whatever position they found themselves in. Some prominent Romans began to advocate for the more humane treatment of slaves. At the same time, there were slave owners who believed that slaves only needed a change of shoes and clothes every two years. Roman courts began to show some leniency towards slaves who came before the courts. Freed slaves still were bound to their former masters, but also enjoyed some benefits and protection. On the death of a slave-owner, slaves were often released.

“Christian” Rome allowed even slaves religious freedom. Once they had done their duties for their masters, they apparently were free to meet with other church members.

After all of these experiences with slavery and captivity, however, leading Jews could still say to Jesus, “We be Abraham’s seed, and have never yet been in bondage to any man” (John 8:33). This Jewish attitude of independence and rebellion against the Romans resulted in the Jewish War of 66 to 73 AD. The Temple was destroyed, and the people were dispersed, thousands of them into slavery. Josephus tells us that as many as 97,000 were marched off to death and captivity. During this captivity, the people were not only very widely dispersed, but they were prevented from returning.

Paul’s ministry throughout the empire took place before the Jewish War, during the Roman peace. During this settled time, even though he was a Roman citizen, Paul suffered a multitude of hardships as he travelled from synagogue to synagogue, from city to city, and from one Roman colony to another. Shipwrecks, beatings and a stoning were only part of his experiences. As we read in his letters, Paul was writing to the churches (or ecclesias, as he called them) preaching about their dealings one with another, whether they were rich or poor, master or slave. The word doulos—slave—is usually translated as servant, but these servants in Paul’s day were not simply people being paid by the hour to serve food, or perform another service. They served in any way, and at any time, that their master demanded. Agricultural work in particular, absorbed a large percentage of the slave population, and literally worked them to death. Excavations at Pompeii uncovered the skeletons of slaves still manacled at the time of death, whose bones revealed the poor nutrition and excessive workload that was their lot in life.

Jesus himself dealt with masters and slaves in Israel. We have the story of the Roman centurion in Luke 7, who contacted Jesus through the Jewish elders to ask him to come to his house in Capernaum and heal his slave, who was very unwell. He then personally sent word to Jesus that there was no need for him to come into the house. He could merely say the word, and the healing would be done. And so it was. The relationship between the Centurion master and his slave was a special one, and it was unusual.

Runaway slaves were a constant problem for Rome. In fact, there were people called fugitovarii, who were specially employed to catch them and return them to their owners. There were many slaves who grasped any opportunity to flee from their masters, as they sought to gain their freedom. Rome, the largest city in the empire, would have been a popular destination, a place where they could hide amongst the crowds.

The Letter to Philemon gives us perhaps a better picture of the situation of slaves in the Empire. Philemon was a believer who Paul had baptized, who looked after a local group of others in his own house in Colosse. He was a master of slaves, and one—Onesimus—had run away. The slave Onesimus had fled to Rome, where he came into contact with Paul. It’s possible that he had met Paul in his master’s house. A baptism was performed, and Paul sent the slave back to his master with the letter we have preserved. Philemon, under Roman law, had the right to deal with his escaped slave in any way he wished. He had the power of life and death over him. But the relationship had now changed. Philemon and Onesimus were to consider themselves brethren in Christ.

In Philemon verses 15 and 16 we read, “For perhaps he therefore departed for a season, that thou shouldest receive him for ever; Not now as a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved, specially to me, but how much more unto thee, both in the flesh, and in the Lord?”

Onesimus was being returned to Philemon, by Paul, not to be punished or put to death, but to be recovered and returned to his place in the household. Jesus and the Apostles did not attack slavery as an institution. They were not driven to emancipate men and women from their social situation. Believers were told to accept their situation.

Paul writes to Timothy:

“Let all who are under a yoke as bondservants (doulos/slaves) regard their own masters as worthy of all honor, so that the name of God and the teaching may not be reviled”

(1 Timothy 6:1 ESV).

To the Colossians, he said:

“Masters treat your bondservants justly and fairly, knowing that you also have a master in heaven” (ch. 4:1 ESV).

As believers, those in the first century had to develop a new attitude towards slavery. We, today, have a duty to serve one another in love.